针对在线学习版块做简单的介绍,文字信息长度不可超过两行

This case begins in the summer, when a man in his 70s with Type II diabetes mellitus and hypertension presented to a hospital with shortness of breath and was found to have an acute infarction of the anterior wall of his heart. He developed several complications, including renal failure from a combination of cardiogenic shock and toxicity from the dye used for emergency catheterization of his heart.

Hemodialysis was started during that hospitalization because of his renal failure. After spending almost a month in the hospital and developing severe deconditioning, he was sent to a sub-acute rehabilitation facility.

From there he requested to be transferred to the Johns Hopkins sub-acute rehabilitation unit, where he spent several weeks. While he was there he was noted to have symptoms consistent with depression, as well as a prior history of a major depressive episode in 1996. Mirtazapine (Remeron) was started. Mirtazapine is a newer antidepressant which is structurally unrelated to other classes of antidepressants. The most common side effect is somnolence.

He was eventually transferred to a skilled nursing unit for another month of rehabilitation management of his medical conditions.

Eventually he was discharged home to the care of his wife. One month or so after leaving the skilled nursing facility he came to our outpatient clinic and requested “a top-to-bottom physical.”

At that time, he was taking Mirtazapine at 30 mg daily (usual dose 15 - 45 mg daily) with 11 other medications. He was very focused on trying to figure out a way to recover from his difficulty with walking. He was still participating in cardiac rehabilitation three mornings a week on the same days as receiving hemodialysis.

He scored 13 out of 30 on the Geriatric Depression Scale. A score greater than 10 suggests an increased risk of a Major Depressive Disorder (Yesavage et al., J Psych Res 1982).

At that visit, the medical team focused on the question of whether he would need to stay on hemodialysis long-term and eliminating unnecessary medications, especially psychotropic medications.

He returned to the clinic and had developed the sense that it was too hard to breath, difficulty sleeping, fatigue, and poor appetite.

He was felt to have congestive heart failure based on these symptoms. His hemodialysis regimen was adjusted, and thoracentesis was performed at the request of his cardiologist. Unfortunately, he ended up in a hospital briefly as a result of a fever he had right after the thoracentesis.

At a clinic visit to follow-up on his hospitalization he looked weaker, and he was admitted to the hospital for more aggressive treatment of his heart failure. There his dialysis regimen was again adjusted, such that 20 pounds of fluid were removed in the course of the first 10 days. It was also established at that time that he would require hemodialysis for the rest of his life.

When he returned to clinic for his post-discharge appointment, his heart failure seemed compensated and his depressed mood became more evident.

At this time, factors that were possibly contributing to his depressive symptoms included:

1. Medical illness: In this case he physical disability complicated by cardiac and renal failure. Other causes such as hypothyroidism were excluded.

2. Other reasons for poor response to treatment were considered. Non-adherence to medication regimen was less likely, thus the question of whether the pharmacology of his antidepressant therapy was altered by his renal failure and dialysis became of interest.

This patient This patient has a history of a major depressive episode. However, by definition depression can not be caused by symptoms attributable to a general medical condition, so in this case many would be uncomfortable attributing his symptoms to a major depressive episode.

Other criteria for a major depressive episode include:

1. Nearly every day - 5 or more out of 9 symptoms, including 1 or more of first tw

2. Duration for >2 weeks or incapacitating (ref: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.)

There were at least two questions, one specific and one general, which this case suggested.

In addition to providing non-pharmacologic treatment, the outstanding questions are:

Let us provide some background before trying to answer these questions.

The definition of ESRD is GFR (glomerular filtration rate) <15.

Reference: U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2004 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, Bethesda, MD, 2004. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government.

What you see on the y axes above are counts or rates of individuals with ESRD in this country. On the x axis you see calendar time, from 1980 to 2002. These graphs suggest that ESRD is rising quickly among older adults. In older adults, almost all these patients with ESRD go on to dialysis, though a very small number get kidney transplants. There are more than 100,000 older patients with ESRD in the US, and older patients make up well over a third of dialysis patients.

Because of differing opinions about whether depressive symptoms can be differentiated from the symptoms of medical illness, as well as the use of different criteria or scales for depression, the estimated prevalence of significant depressive symptoms varies widely. Probably around 15% is a good figure for prevalence of depression in hemodialysis patients. Interestingly, the rate of suicidality is only slightly higher than in the general population.

Given this background, we hope you are interested in the clinical questions that have been posed. Let us return to them and try to provide responses.

In order to try to answer the two clinical questions, we first turned to the prior systematic reviews of evidence. Unfortunately, this did not yield useful information. The literature on this topic, which is remarkably limited, falls into two categories: brief reports of pharmacokinetics of antidepressants in dialysis patients, and, studies with few patients in the treatment arms (5-12 patients per study) which look at whether treatment is beneficial. None of the studies look at both pharmacokinetics and clinical outcomes simultaneously.

Finally, we also turned to sources of background knowledge in order to try to answer these questions. In short, there is some evidence, but it is limited with respect to the ability to propose a standard of care.

The table below shows commonly used antidepressants and the recommendations for dosing in geriatric patients as well as patients with ESRD or hemodialysis.

The columns are for commonly used antidepressant medications. The rows contain recommendations gathered from the abovementioned sources. Note the amount of missing information. Note also that even in medications where no change in dose in a dialysis patient is recommended there may be reason for caution on the basis of advanced age or impaired kidney function.

Drug | Dialysis Dosing | Dosing in Renal Insufficiency | Geriatric Dosing |

Citalopram | same | use with caution | decrease |

Escitalopram | - | decrease dose | 50% |

Fluoxetine | same | same | lower initial dose or longer frequency |

Paroxetine | - | decrease in severe | decrease |

Sertraline | same/decrease frequency | same | no specific recommendations |

Nefazodone | - | - | start at low dose 100 md/day |

Trazodone | - | same | decrease in men |

Venlafaxine | 50% dosed 4 hours after HD | decrease dose | decrease |

Mirtazapine | - | decrease dose | decrease in men |

Nortriptyline | same | same | effective at lower dose and plasma concentration |

Bupropion | - | studies not done | same |

In summary then, the following points may be suggested.

Remember that for Nortriptyline there is evidence that lower doses and serum concentrations are effective at treating depression in older patients compared to young patients.

This summary reveals that there are gaps in the current “evidence base.” So, we are left with the scientific application of judgment.

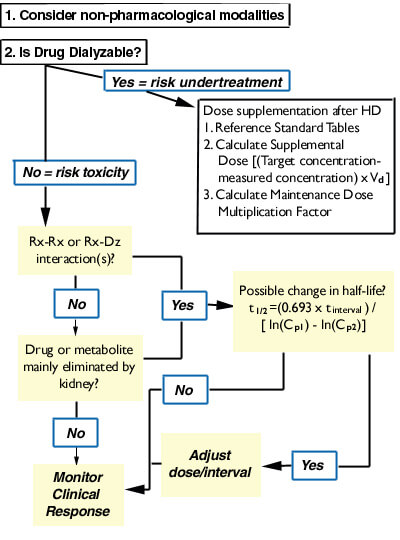

The following clinical algorithm is offered in the hopes of providing a simple yet robust approach to treating these complex patients.

If a drug is dialyzable (an infrequent case among drugs used for depression - but Lithium is an example), then there is risk of under-treatment. Note that there are 3 alternative ways to estimate how to supplement dosing if a drug is significantly removed by dialysis. Also remember that some drugs may be effective at lower serum concentrations in older patients.

Ironically, in this particular case, when the patient returned to clinic in December his symptoms had markedly improved without a change in medication. He was also doing much better physically.

To break this down even further, 2 take home points may be suggested:

This module has hopefully used a clinical case drawn from real life to exemplify the following general principles of pharmacologic management in an older patient on hemodialysis:

In addition, we hope the reader has developed an appreciation of the complex nature of caring for older patients with multiple diseases. Many older patients like our example wend their way through a complex health care system which includes multiple sites of care and different clinicians. It can often be difficult to attribute symptoms to a single disease, which means that therapeutic strategies must often take a stepwise approach. There is a lot of “unmapped territory” where evidence shedding direct light on how to care for these patients has not been created.